『DDIA』- CH07: Transactions Reading Notes

29 Jan 2019 | DDIA | booknotesCreated to simplify the programming model for applications accessing a database. ACID: Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability.<\br> BASE: Basically Available, Soft state, Eventual consistency.

Atomicity

In general: something cannot be broken down into smaller parts. Multi-threaded programming: the system can only be in the state it was before the operation or after the operation, not something in between. In ACID, not concurrency. The ability to abort a transaction on error and have all writes from that transaction discarded.

Consistency

You have certain statements about your data that must always be true.

Isolation

Race conditions. Serialability: Each transaction can pretend that it is the only transaction running on the entire database. The database ensures that when the transactions have committed, the result is the same as if they had run serially. -> Seldom used because of performance penalty.

Durability

Single-node: the data has been written to nonvolatile storage such as SSD. Replicated: the data has been successfully copied to some number of nodes.

Single-Object and Multi-Object Operations

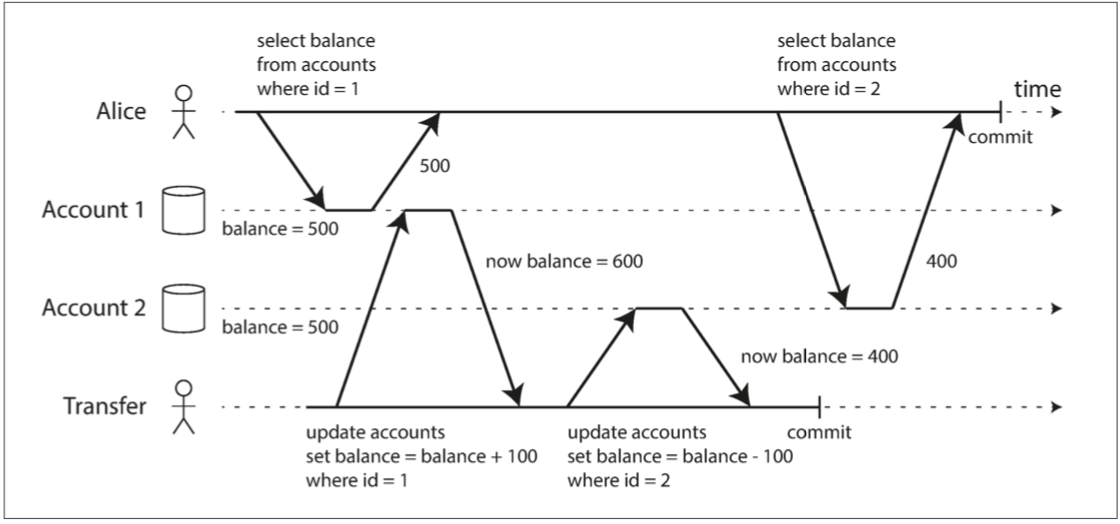

select count(*) from emails where recipient_id = 2 and unread_flag = true With a saperated unread emails counter.

The email counter and the updated mailbox should be bind together. If violated, user may see unread mail count, but end up with an empty mail box.

Single object operation

- recovory log

- increment operation

- compare-and-set

Multi-object transactions

Foreign key reference, denormalized documents, secondary indexes… Considering of error handling.

Weak Isolation Levels

Why weak? Serializable isolation costs too much in many systems.

Read Committed

The most basic level.

Two guarantees:

- When reading from the database, you will only see data that has been committed (no dirty reads)

- When writing to the database, you will only overwrite data that has been committed (no dirty writes)

Implementation options:

- Prevent dirty writes by using row-level locks, only one transaction can hold the lock for any given object.

- Prevent dirty reads with row-level locks: do not work well in practice, because one long-running write transaction can force many read-only transactions to wait.

- Prevent dirty reads by holding both old value and new value of the ongoing transaction. When transaction not committed, reads can get old value.

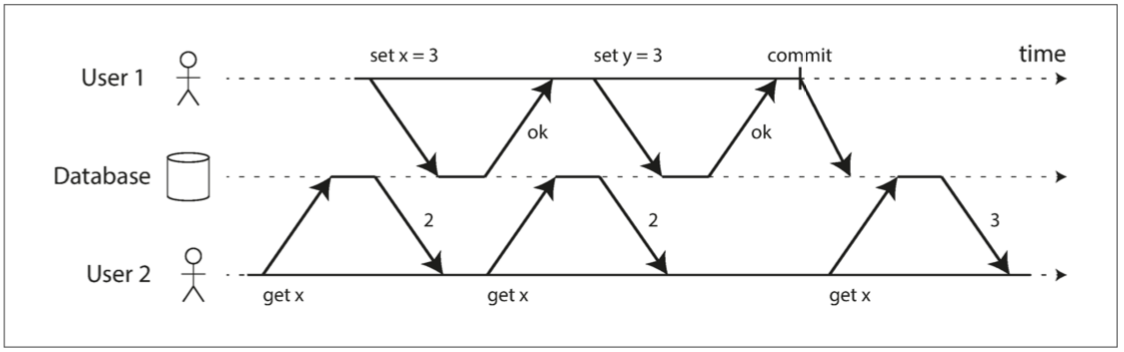

Snapshot Isolation and Read

Problem to be solved is called nonrepeatable read or read skew.

Solution: snapshop isolation. Each transaction reads from a consistent snapshot of the database. Boon for long-running, read-only queries such as backups and analytics.

Implementation:

- Readers never block writers, and writers never block readers

- Maintains several versions of snapshot: multi-version concorrency control

How do indexes work in a multi-version datavase?

- Index simply point to all versions of an object and require an index query to filter out ant obj versions that are not visible

- B-Trees with append-only/copy-on-write variant that do not overwrite pages of the tree when they are updated, but instead creates a new copy of each modified page. Parents pages, up tp the root of the tree, are copied and udpated to point to the new versions of their child pages. (compaction & gc)

Preventing Lost Updates

Think about scenarios which read - modify - write back can happen.

UPDATE counters SET value = value + 1 WHERE key = ‘foo’;

-

Atomic write operations are supported by most relational databases. Usually implemented by taking an exclusive lock on the object when it is read so that no other transaction can read it until the udpate has been applied. -> cursor stability.

- Explicit locks in application prevent lost updates by locking all rows returnd by database

- Execute read-modify-write cycles in parallel and, if the transaction manager detects a lost update,abort the transaction and force it to retry its cycle. Implement in conjunction with snapshot isolation: PostgreSQL’s repeatable read, Oracle’s serializable, and SQL Server’s snapshot isolation. Not MySQL/InnoDB’s repeatable read.

- Compare-and-set’s safety depends on database’s implementation, if the database allows the WHERE clause to read from an old snapshot, then the statement may not prevent lost updates.

UPDATE wiki_pages SET content = ‘new content’ WHERE id = 1234 AND content = ‘old content’;

- Detect concurrent writes in conflict resolution and replication

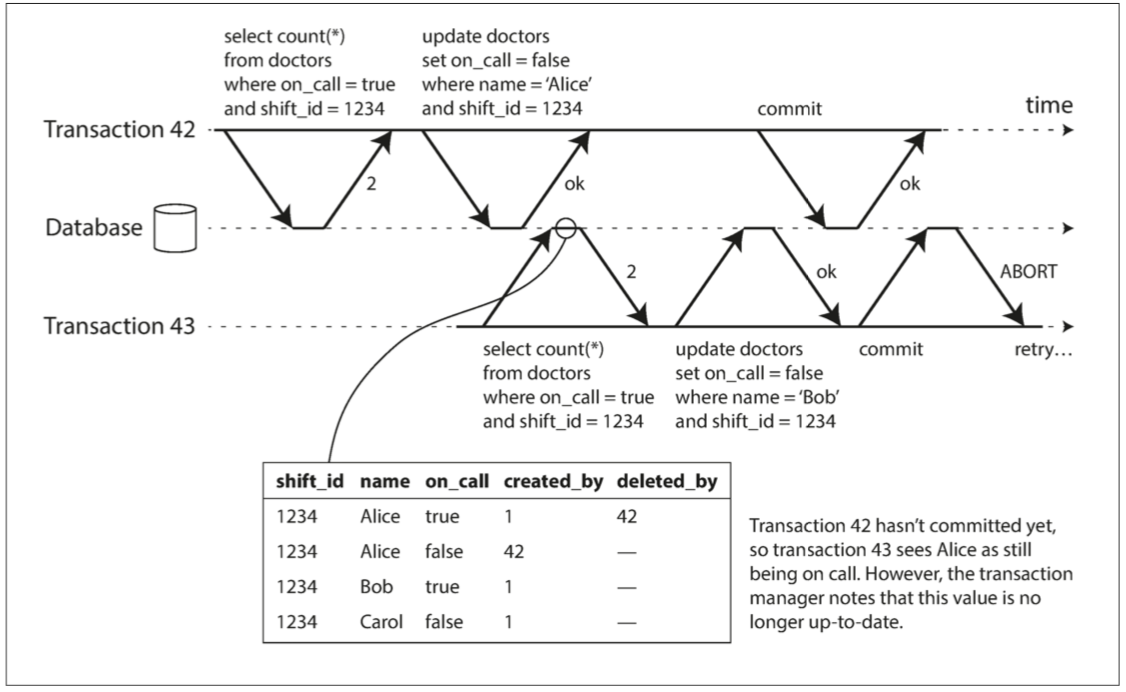

Write Skew and Phantoms

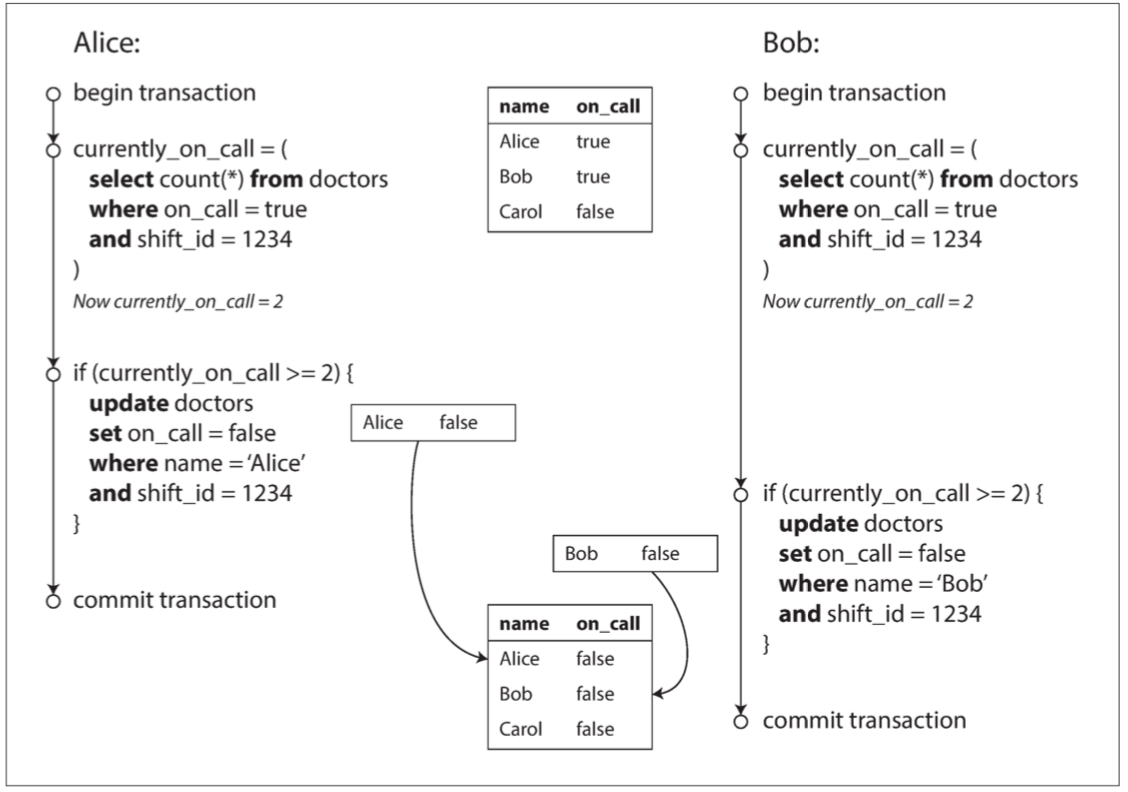

Since the database is using snapshot isolation, both checks reture 2 and proceeds to the next udpate.

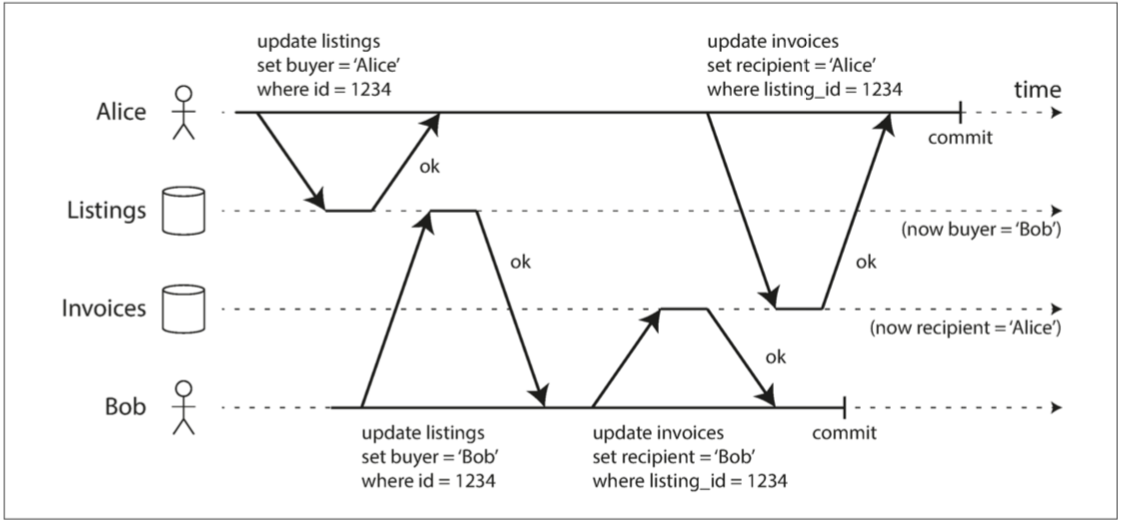

Write skew: it is neither a dirty write nor a lost update because the two transactions are updating two different objects.

No help:

Since the database is using snapshot isolation, both checks reture 2 and proceeds to the next udpate.

Write skew: it is neither a dirty write nor a lost update because the two transactions are updating two different objects.

No help:

- Atomic single-object operation

- Automatic detection of lost updates Help:

- Constriants implemented with triggers or materialized views depending on the database

- Explicitly lock the rows that the transaction depends on.

Materializing conflicts: takes a phantom and turns it into a lock conflict on a concrete set of rows that exist int the database. But this approach should be considered a last resort if no alternative is possible.

Serializability

Most databases provide serializability today use one of three techniques:

- Literally executing transactions in a serial order

- Two-phase locking

- Optimistic concurrency control techniques such as serializable snapshot isolation

In this context, the following discussion will be based on single-node databases.

Actual Serial Execution

Remove the concurrency entirely. Single-thread execution was only decided feasible recently, and what changed to make it possible?

- RAM cheap enough to keep the entire active dataset in memory.

- Designers realized that OLTP transactions are usually short and only make a small number of reads and writes, while long-running analytic queries are typically read-only.

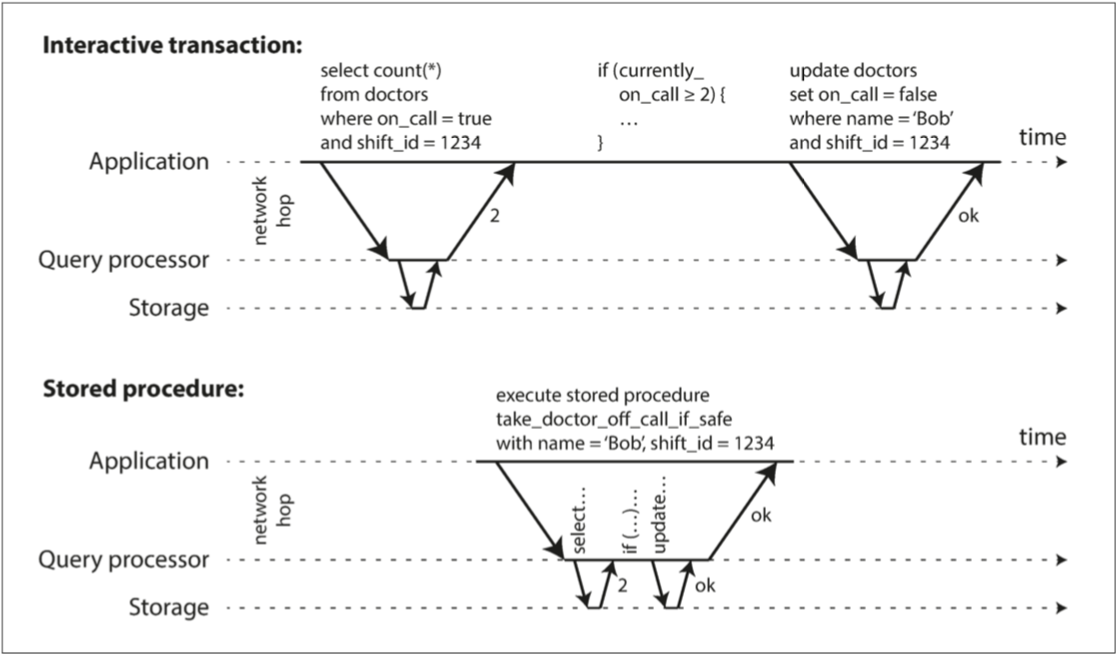

Thinking about a long and human interactive scenario of booking airplane ticket, it is reasonable to break the whole long transaction into multiple concurrent small transactions, and submit whole transaction as stored process. If all needed data are ready, the stored process can be executed fast without waiting for disk resource or network.

Some bad reputations of stored procedures:

- Each database vendor own its archaic language lacking the ecosystem of libraries

- Code running in a database is difficult to manage

- Database is more performance-sensitive, so it can cause much more trouble when there is a badly written stored procedure

Leverage partition to increase performance of serialization. Fetch data from single transaction is fast, but cross partitions will be much slower.

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

Not two-phase commit.

- If transaction A has read an object and transaction B wants to write to that object, B must wait until A commits or aborts before it can continue. (This ensures that B can’t change the object unexpectedly behind A’s back.)

- If transaction A has written an object and transaction B wants to read that object, B must wait until A commits or aborts before it can continue. (Reading an old version of the object, like in Figure 7-1, is not acceptable under 2PL.)

Diff between 2PL and snapshot isolation:</br>Snapshot isolation has the mantra readers never block writers, and writers never block readers.

The lock can either be in shared mode or in exclusive mode. The lock is used as follows: • If a transaction wants to read an object, it must first acquire the lock in shared mode. Several transactions are allowed to hold the lock in shared mode simulta‐ neously, but if another transaction already has an exclusive lock on the object, these transactions must wait. • If a transaction wants to write to an object, it must first acquire the lock in exclu‐ sive mode. No other transaction may hold the lock at the same time (either in shared or in exclusive mode), so if there is any existing lock on the object, the transaction must wait. • If a transaction first reads and then writes an object, it may upgrade its shared lock to an exclusive lock. The upgrade works the same as getting an exclusive lock directly. • After a transaction has acquired the lock, it must continue to hold the lock until the end of the transaction (commit or abort). This is where the name “two- phase” comes from: the first phase (while the transaction is executing) is when the locks are acquired, and the second phase (at the end of the transaction) is when all the locks are released.

Predicate Lock

Belongs to all objects that match some search condition.

SELECT * FROM bookings WHERE room_id = 123 AND end_time > ‘2018-01-01 12:00’ AND start_time < ‘2018-01-01 13:00’;

It applies event to objects that do not yet exist in the database, but which might be added in the future (phantoms).

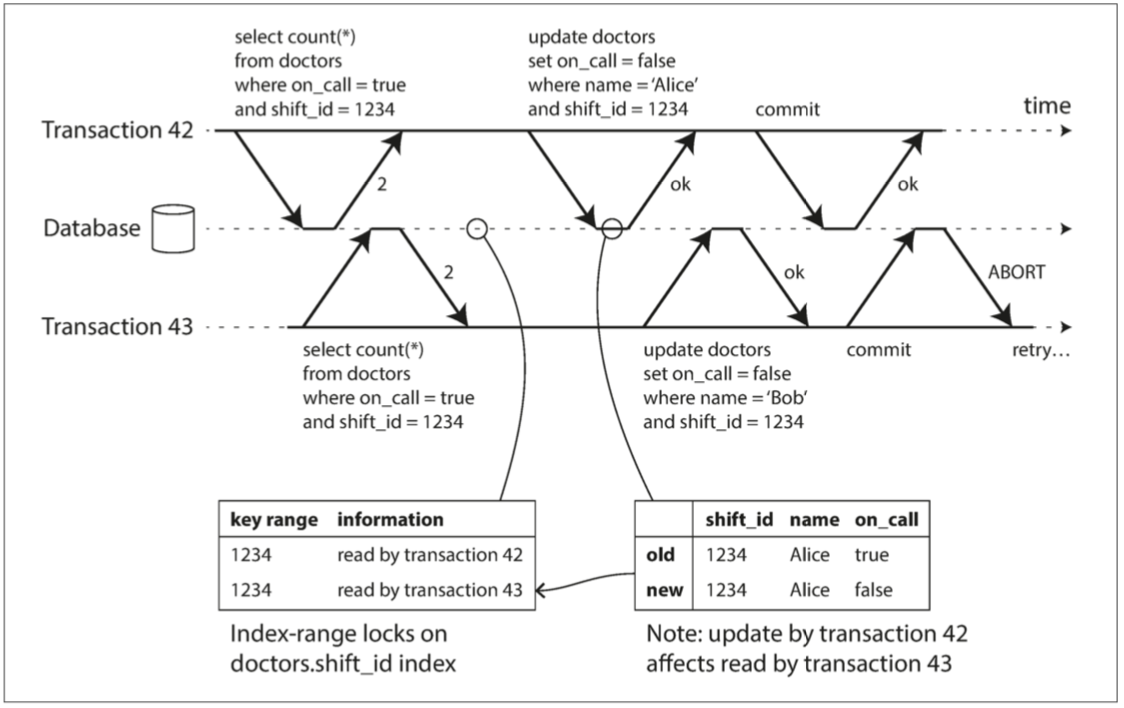

Index-range locks - simplified approximation of predicate locking

To use less locks, we can approximate the range by using single index, eg. Booking a room 123 between 12 to 1 pm, we can use room index 123 to lock all time range for this room. If there is no suitable index where a range lock can be attached, the database can fall back to a shared lock on the entire table.

Serializable Snapshot Isolation

Provides full serializability with small performance penalty. 2PL is pessimistic concurrency control mechanism, serial execution is pessimistic to the extreme. SSI is an optimistic technique: transactions continue anyway,in the hope that everything will turn out all right. When a transaction wants to commit, db checks if anything bad happend and need abortion and retry.

query + update How does the db know if a query result might have changed?

- Detecting reads of a stale MVCC object version

- Detecting writes that affect prior reads